Lista (incompleta) degli articoli storici e imprescindibili per ogni founder

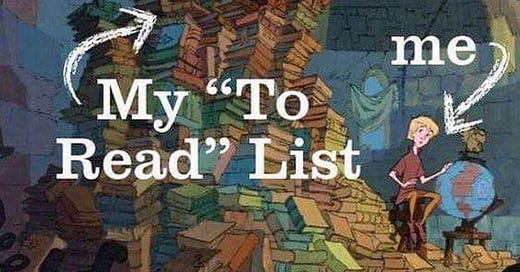

Per chi è curioso, ha voglia di imparare, o è in panciolle sotto l'ombrellone o in montagna.

Alcune premesse veloci veloci perché questo è un articolo lungo.

"Le liste sono già vecchie ancora prima di iniziare" fu il commento che fece la mia capa, più di dieci anni fa, a un articolo che volevo scrivere. Aveva ragione, però anche torto. Aveva ragione perché la maggior parte delle liste non invecchia bene, veramente non sono più aggiornate dopo pochissimo tempo. Però ci sono alcune liste, quelle che elencano per esempio dei pezzi storici di una specifica cultura, o che organizzano le basi del sapere di uno specifico settore, quelle secondo me sono liste preziosissime e sempre di grande valore. Qui non ho la presunzione di realizzare una cosa del genere, ma penso che questa lista possa essere utile ai founder — soprattutto se all'inizio della loro esperienza — per lungo tempo. Alcuni di questi articoli io li leggo periodicamente, e ogni volta ne trovo spunti nuovi.

Questa non è una lista esaustiva, anzi. Sono quelli che sono venuti in mente a me, alcuni di quelli che ho messo tra i preferiti negli ultimi 10 anni. Mi piacerebbe, se vi va, raccogliere anche i vostri spunti. Quali sono gli articoli che secondo voi fanno parte della knowledge base fondamentale per un founder (o per chiunque si occupi di innovazione o investimenti)?

È una lista abbastanza lunga, non è immaginata perché venga per forza consumata tutta d'un fiato, anzi. Spero, essendo io una grande ottimista 😅, che salviate questa pagina da qualche parte, e che la torniate a leggere quando avete voglia di imparare qualcosa. Non da me eh, ma da tutte le menti meravigliose che sono raccolte qui dentro. Se potete, con calma, e se ne avete voglia, cliccate sull'articolo originale, e andate ad approfondire leggendo tutto il testo. Soprattutto quelli di Paul Graham - anche se lunghi - elaborano dei concetti secondo me indimenticabili, quelli che entrano a far parte in modo permanente del pensiero di chi li legge (o almeno per me è stato così).

Last but not least, una piccola nota superficiale: diversi di questi articoli sono considerati imprescindibili, soprattutto qua in Silicon Valley, per founder e investitori (e manager di acceleratori, e open innovation manager, eccetera eccetera...). Vengono citati spessissimo nelle conversazioni sia lavorative che sociali - sì, qua non si parla d'altro, perfino fuori dall'asilo di mia figlia i genitori parlano di startup 😵 - quindi vi capiterà sicuramente che qualcuno faccia un riferimento a uno di questi pezzi. Non fatevi cogliere impreparati, annuendo con lo sguardo perso. Cogliete le citazioni e sentitevi degli insider sapendo di cosa si sta parlando 😎. Lo so che sembra un motivo frivolo, ma non sentirsi esclusi con riferimenti che non comprendete è già un passo avanti per inserirvi in un contesto che vi interessa.

Qui l’elenco degli articoli in questo post, per ognuno di questi, se scrollate giù, trovate un mio commento e qualche piccolo estratto dal testo originale, per capire se è il vostro genere (in più ovviamente il link all’articolo originale per approfondire):

Do things that don't scale - Paul Graham

Maker's Schedule, Manager's Schedule - Paul Graham

Why Software Is Eating the World - Marc Andreessen

Peacetime CEO/Wartime CEO - Ben Horowitz

We Don’t Sell Saddles Here - Stewart Butterfield

The Only Thing That Matters - Marc Andreessen

Why Startups Need to Focus on Sales, Not Marketing - Jessica Livingston

Fundraising Mistakes Founders Make - Sam Altman

1,000 True Fans - Kevin Kelly

Amazon's original 1997 letter to shareholders - Jeff Bezos

[Bonus track] Life is short - Paul Graham

Fine premessa, andiamo alla ciccia!

Do things that don't scale - Paul Graham

Questo secondo è uno dei essays più belli di Paul Graham - sicuramente uno di quelli che io ho inviato di più ad amici e colleghi.

Una volta letto capirete i riferimenti che spesso sentirete nelle chiacchierate tra tech enthusiast a "Collison installation" o "to pull a Meraki".

Parla degli inizi di una startup, consiglia di non concentrarsi sul rendere il processo di recruiting degli utenti scalabile, ma di concentrarsi più sulla crescita stabile degli utenti, serenamente tramite recruiting manuale.

"Startups building things for other startups have a big pool of potential users in the other companies we've funded, and none took better advantage of it than Stripe. At YC we use the term "Collison installation" for the technique they invented. More diffident founders ask "Will you try our beta?" and if the answer is yes, they say "Great, we'll send you a link." But the Collison brothers weren't going to wait. When anyone agreed to try Stripe they'd say "Right then, give me your laptop" and set them up on the spot."

Stesso discorso per i processi (facendo l'esempio di Stripe che approvava gli "instant account" in modo manuale):

"When you only have a small number of users, you can sometimes get away with doing by hand things that you plan to automate later. This lets you launch faster, and when you do finally automate yourself out of the loop, you'll know exactly what to build because you'll have muscle memory from doing it yourself."

Poi si focalizza sull'ossessione che i founder devono avere per rendere l'esperienza dei propri clienti la migliore possibile.

"It's not the product that should be insanely great, but the experience of being your user. The product is just one component of that. For a big company it's necessarily the dominant one. But you can and should give users an insanely great experience with an early, incomplete, buggy product, if you make up the difference with attentiveness."

Maker's Schedule, Manager's Schedule - Paul Graham

Altra perlona di Paul Graham. Questo è un post che in qualche modo esplicita una cosa che abbiamo tutti nel retrocranio, e le dà un nome. È un post utile sia per manager che per maker, perché spesso una startup è fatta da entrambi i soggetti, o sicuramente si deve interfacciare con entrambi i soggetti. E avere in mente questo semplice concetto di come fare convivere le due tipologie di organizzazione della giornata è molto importante.

La manager's schedule è quella di chi generalmente organizza il lavoro (e non "crea", come un manager), ma anche quella di un VC, di un angel, di un direttore di un accelerator. È una giornata lavorativa organizzata in blocchi da 20-30-60 minuti, tutti autonomi tra loro, in cui incastrare riunioni, review di documenti, risposte a mail. Sono tutti task brevi e ben incastrabili tra loro, che non interrompono la concentrazione o il flusso del lavoro:

There are two types of schedule, which I'll call the manager's schedule and the maker's schedule. The manager's schedule is for bosses. It's embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. When you use time that way, it's merely a practical problem to meet with someone. Find an open slot in your schedule, book them, and you're done.

Poi c'è la maker's schedule, che è quella di chi invece crea, di chi ha bisogno di una concentrazione profonda e prolungata per portare a compimento un'unità di lavoro, per cui le unità di tempo lavorativo si misurano almeno in mezze giornate: pensiamo a sviluppatori, ingegneri, scrittori, content creator. Per queste persone anche una sola riunione da mezz'ora, piazzata nel mezzo della mattina o del pomeriggio, può far saltare una mezza giornata di lavoro (o può rovinare il mood di un'intera giornata):

But there's another way of using time that's common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can't write or program well in units of an hour. That's barely enough time to get started. When you're operating on the maker's schedule, meetings are a disaster. A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in.

Il problema nasce quando queste due tipologie di persone devono interagire (tipicamente founder e VC) o quando una persona normalmente nella manager's schedule ha invece bisogno di tempistiche da maker e quindi deve rivoluzionare il suo modo di interagire con gli altri.

Nel pezzo si approfondiscono questi scenari con le soluzioni che PG ha trovato per sé.

Ottimo food for thoughts.

Why Software Is Eating the World - Marc Andreessen

Questo pezzo storico, scritto da Marc Andreessen, fondatore di Netscape e founder e partner della VC firm Andreessen-Horowitz (a16z), risale al 2011, dieci anni fa.

Il tema è: con tutte queste tech companies che stanno crescendo in verticale (Facebook, Twitter...) siamo davanti a una nuova dot.com bubble? Lui spiega perché no.

We believe that many of the prominent new Internet companies are building real, high-growth, high-margin, highly defensible businesses.

But too much of the debate is still around financial valuation, as opposed to the underlying intrinsic value of the best of Silicon Valley’s new companies. My own theory is that we are in the middle of a dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies are poised to take over large swathes of the economy.

Ma perché questo grande successo proprio ora? Perché sono passati sessant'anni dall'inizio della rivoluzione informatica, quarant'anni dall'invenzione del microprocessore e vent'anni dall'avvento della moderna Internet, e quindi tutta la tecnologia necessaria per trasformare le industrie attraverso il software finalmente funziona e può essere ampiamente distribuita su scala globale (ovviamente si riferisce al 2010).

With lower start-up costs and a vastly expanded market for online services, the result is a global economy that for the first time will be fully digitally wired — the dream of every cyber-visionary of the early 1990s, finally delivered, a full generation later.

Poi continua con esempi: il più grande venditore di libri è una software company (Amazon), il più grande distributore di film e video è una software company (Netflix), il più grande distributore di musica è una software company (iTunes e Spotify), le più importanti aziende nel campo dell'intrattenimento sono software e producono videogame (lui prende come esempio Zynga, oggi diremmo Roblox probabilmente). E ancora:

fotografie = Shutterfly, Snapfish, Flickr, Instagram (ciao Kodak)

lungometraggi animati = Pixar (Disney se l'è dovuta comprare)

telecomunicazioni = Skype, Zoom, Whatsapp

recruiting = Linkedin

advertisement = Facebook, Google

Tutte software companies.

Poi un po' di sano American dream:

It’s not an accident that many of the biggest recent technology companies — including Google, Amazon, eBay and more — are American companies. Our combination of great research universities, a pro-risk business culture, deep pools of innovation-seeking equity capital and reliable business and contract law is unprecedented and unparalleled in the world.

E poi conclude:

Instead of constantly questioning their valuations, let’s seek to understand how the new generation of technology companies are doing what they do, what the broader consequences are for businesses and the economy and what we can collectively do to expand the number of innovative new software companies created in the U.S. and around the world.

That’s the big opportunity. I know where I’m putting my money.

Dieci anni dopo è ancora tutto vero e attuale, forse più che mai, e Marc Andreessen ha costruito un impero VC su tutte queste sue intuizioni (ha appena raccolto un fondo da 2.2 miliardi di dollari, il terzo, per investire in crypto).

Peacetime CEO/Wartime CEO - Ben Horowitz

Come potrete immaginare dal nome Ben Horowitz è l'altra metà della VC firm Andreessen-Horowitz (di cui parlavo sopra).

Anche questo è un articolo del 2011, ma continua a essere estremamente rilevante.

Descrive la differenza tra un Peacetime CEO - un CEO adatto a guidare l'azienda in momenti di grande vantaggio competitivo, grande crescita ed espansione - e un Wartime CEO - che invece guida l'azienda quando il gioco "si fa duro" e l'azienda è davanti a un grosso bivio o una grossa minaccia (come un competitor più innovativo o un cambiamento improvviso del mercato).

Per Google il Peacetime CEO era Eric Schmidt, mentre il Wartime CEO Larry Page (nel frattempo è cambiato di nuovo, dal 2015 è Sundar Pichai).

La stessa persona può essere in alcuni momenti peacetime CEO e in altri wartime. Anche se è molto difficile che sia efficace in entrambe le situazioni.

In my personal experience, I was a peacetime CEO for about 9 months, then a wartime CEO for the next 7 years. My greatest management discovery through that transition was that peacetime and wartime require radically different management styles.

I peacetime CEO devono massimizzare e ampliare l'attuale opportunità. Che significa incoraggiare la creatività, l'intraprendenza, il contributo individuale di ognuno. Nella gestione del wartime CEO, invece, l'azienda ha tipicamente un solo proiettile in camera e deve, a tutti i costi, colpire il bersaglio. La sopravvivenza dell'azienda in quel caso dipende dalla stretta aderenza e allineamento alla missione di ognuno.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple, the company was weeks away from bankruptcy—a classic wartime scenario. He needed everyone to move with precision and follow his exact plan; there was no room for individual creativity outside of the core mission. In stark contrast, as Google achieved dominance in the search market, Google’s management fostered peacetime innovation by enabling and even requiring every employee to spend 20% of their time on their own new projects.

Qualche esempio pratico, nell'articolo ce ne sono tanti:

Peacetime CEO focuses on the big picture and empowers her people to make detailed decisions. Wartime CEO cares about a speck of dust on a gnat’s ass if it interferes with the prime directive.

Peacetime CEO knows that proper protocol leads to winning. Wartime CEO violates protocol in order to win.

Peacetime CEO thinks of the competition as other ships in a big ocean that may never engage. Wartime CEO thinks the competition is sneaking into her house and trying to kidnap her children.

Lo spunto interessante per ogni CEO è capire se si sentono più peacetime o wartime CEO, e di conseguenza quando (e se) cedere il passo a qualcuno di più adatto in momenti opposti.

Della stessa tipologia consiglio anche Good Product Manager/Bad Product Manager, sempre di Ben Horowitz.

We Don’t Sell Saddles Here - Stewart Butterfield

Questo post è per tutti quelli che stanno per lanciare il loro prodotto (o hanno nel loro futuro, prossimo o meno, il lancio di un prodotto).

Stewart Butterfield è il co-founder di Flickr e di Slack. Questo articolo riporta il memo del 2013 mandato al team originario di Slack due settimane prima del lancio sul mercato.

Parla, con una lucidità e una visione illuminanti, di come costruire una "customer base" e davvero raggiungere i propri utenti, per arrivare al tanto agognato product/market fit.

Just as much as our job is to build something genuinely useful, something which really does make people’s working lives simpler, more pleasant and more productive, our job is also to understand what people think they want and then translate the value of Slack into their terms.

Il concetto principale dell'articolo è che non si può vendere un prodotto, soprattutto software, in quanto "prodotto software", ma per quello che rappresenta e per il mercato che crea. Quindi Slack non deve essere una "chat di gruppo per il lavoro", ma il modo per "migliorare la comunicazione della propria azienda, prendere decisioni più velocemente, ridurre le mail".

We are unlikely to be able to sell “a group chat system” very well: there are just not enough people shopping for group chat system. [...]What we are selling is not the software product — the set of all the features, in their specific implementation — because there are just not many buyers for this software product. However, if we are selling “a reduction in the cost of communication” or “zero effort knowledge management” or “making better decisions, faster” or “all your team communication, instantly searchable, available wherever you go” or “75% less email” or some other valuable result of adopting Slack, we will find many more buyers.

Il titolo "we don't sell saddles here" viene proprio da questo concetto: se vendessimo selle non dovremmo concentrarci sul promuovere la qualità della manifattura o della pelle usata per costruirle, ma direttamente sulla promozione dell'horseback riding, dell'equitazione, posizionandoci come leader. Perché se le persone si innamoreranno dell'equitazione, inevitabilmente poi verranno a cercare delle selle (in particolare dal leader di mercato).

To see why, consider the hypothetical Acme Saddle Company. They could just sell saddles, and if so, they’d probably be selling on the basis of things like the quality of the leather they use or the fancy adornments their saddles include; they could be selling on the range of styles and sizes available, or on durability, or on price. Or, they could sell horseback riding. Being successful at selling horseback riding means they grow the market for their product while giving the perfect context for talking about their saddles. It lets them position themselves as the leader and affords them different kinds of marketing and promotion opportunities (e.g., sponsoring school programs to promote riding to kids, working on land conservation or trail maps). It lets them think big and potentially be big.

Infine un importantissimo reminder per tutti i team tecnici là fuori:

We are an exceptional software development team. But, we now also need be an excellent customer development team. That’s why, in the first section of this doc, I said “build a customer base” rather than “gain market share”: the nature of the task is different, and we will work together to understand, anticipate and better serve the people who trust us with their teams’ communications, one customer at a time.

The only thing that matters - Marc Andreessen

Di nuovo Marc Andreessen, per chiudere in bellezza. Questo post - a differenza di quello citato prima che veniva dal blog di a16z - viene dal blog originale di Andreessen, blog.pmarca.com, che ora è offline, e che è stato salvato in questo archivio: pmarchive.com. Sono quasi tutti post scritti tra il 2007 e il 2009 (praticamente più di 10 anni fa, che su internet sono ere geologiche) ma ancora preziosissimi. Soprattutto consiglio tutta la serie "The pmarca guide to startups", in 9 parti, da cui viene anche l'articolo che vi consiglio.

Per chi preferisce qui c'è il pdf raccolto da a16z con tutti gli articoli migliori dal vecchio blog di Marc Andreessen.

Ma torniamo al nostro post originario: il titolo - L'unica cosa che conta - si riferisce ancora al tanto agognato product/market fit

In a great market -- a market with lots of real potential customers -- the market pulls product out of the startup.

The market needs to be fulfilled and the market will be fulfilled, by the first viable product that comes along.

Andreessen parla dell'importanza del trovare il giusto mercato - che sta aspettando proprio questo prodotto ed è pronto ad acquistarlo, del PMF come un momento così importante tanto da dividere la vita di una startup in BPMF (before product/market fit) e APMF (after product/market fit).

When you are BPMF, focus obsessively on getting to product/market fit.

Do whatever is required to get to product/market fit. Including changing out people, rewriting your product, moving into a different market, telling customers no when you don't want to, telling customers yes when you don't want to, raising that fourth round of highly dilutive venture capital -- whatever is required.

When you get right down to it, you can ignore almost everything else.

Why Startups Need to Focus on Sales, Not Marketing - Jessica Livingston

Se siete tra i "1000 true fans" del Dojo (per la cit. vedere sotto) sapete già chi è Jessica Livingston. Ne abbiamo parlato qui, essendo lei una delle colonne portanti di Y Combinator dalle sue origini.

In questo articolo, pubblicato originariamente nel 2014 sul Wall Street Journal (ma ora con paywall quindi, ve ne ho linkata un'altra versione), parla di una verità conosciuta dalla maggior parte dei founder, ma sempre un po' scomoda: è cioè che all'inizio bisogna concentrarsi sulle vendite, non sul marketing. E che il founding team è quello che deve vendere, non un sales team assunto apposta (non all'inizio e non per le prime vendite).

The kind of marketing you should be doing should be indistinguishable from sales: you should be talking to a small number of users who are seriously interested in what you’re making, not a broad audience who are on the whole indifferent.

Anche qui lei cita la "Collison installation" dei fratelli Collison di Stripe 😂

So why wouldn’t all founders start by engaging with users individually? Because it’s hard and demoralizing. Sales gives you a kind of harsh feedback that “marketing” doesn’t. You try to convince someone to use what you’ve built, and they won’t. These conversations are painful, but necessary. I suspect from my experience that founders who want to remain in denial about the inadequacy of their product and/or the difficulty of starting a startup subconsciously prefer the broad and shallow “marketing” approach precisely because they can’t face the work and unpleasant truths they’ll find if they talk to users.

Generalmente i founder, soprattutto se tecnici, odiano vendere. Odiano occuparsi della parte commerciale, odiano bussare alle porte, odiano chiedere soldi. Quindi questo articolo è sempre un reminder doveroso.

Fundraising Mistakes Founders Make - Sam Altman

Anche qui i lettori del Dojo non troveranno niente di estremamente nuovo, ma Sam Altman queste cose le ha dette meglio e prima (l'articolo è del 2014 - anche se alcune cose, tipo la considerazione sui party round, oggi sono un po' datate).

The process is simple:

1. Get intros to investors you want to talk to and reach out to them, in parallel, not in series - this is important, see (3).

2. Explain to them why your company is likely to make them a lot of money.This usually includes the company’s mission, the product, current traction, future vision, the market, the competition, why you’re going to win, what the long-term competitive advantage will be, how you’re going to make money, and the team.

3. Set up a competitive environment. You'll (unsurprisingly) get the best terms when multiple investors compete with one another for space in your round. This is the one rule of "the game" that is really important.

L'articolo riassume, in maniera sintetica e chiara, indicazioni molto utili da tenere presente se si è interessanti a iniziare una raccolta.

Netflix Culture Manifesto

Questo non è un articolo, ma rimane secondo me uno dei capisaldi della cultura imprenditoriale attuale.

Se siete interessati al tema di culture & welfare aziendale (e spero di sì perché personalmente mi appassiona molto) trovate un articolo che ho scritto qui sul Dojo un po' di tempo fa: Work smarter, not harder: il welfare aziendale della Silicon Valley

Come dice Augusto Marietti in questo video parlando della cultura aziendale di Kong: "you're going to get a culture either way, so you better kind of work on it, so you get it really true to your principles". Che significa che una cultura aziendale si crea che il founding team lo faccia in modo intenzionale o meno, quindi meglio esserne consapevoli e guidare il processo della sua creazione perché aderisca più possibile ai propri principi. Sembra un concetto banale esplicitato così, ma nella realtà dei fatti delle aziende (soprattutto nate da 10+ anni, soprattutto in Italia) non lo è affatto.

Tornando a Netflix, questa pagina esplicita i valori, le relazioni, le libertà e le responsabilità che stanno alla base della cultura aziendale. Secondo me è un'opera d'arte, imprescindibile per ogni founder, che si concordi con i suoi principi o meno.

Like all great companies, we strive to hire the best and we value integrity, excellence, respect, inclusion, and collaboration. What is special about Netflix, though, is how much we:

encourage independent decision-making by employees

share information openly, broadly, and deliberately

are extraordinarily candid with each other

keep only our highly effective people

avoid rules

Anche solo per il fatto che tutti questi valori siano stati messi nero su bianco rende in automatico ogni componente dell'azienda accountable (traducibile in modo non preciso con "responsabile") per il proprio modo di essere e comportarsi con i propri colleghi. Fissando esplicitamente obiettivi e valori così alti e positivi, si alza l'asticella per tutti. Ed è un'asticella bellissima da alzare, ce ne fossero di imprese che si impegnano a creare un ambiente di lavoro così libero, positivo ed empowering.

It’s easy to write admirable values; it’s harder to live them. In describing courage we say, “You question actions inconsistent with our values.” We want everyone to help each other live the values and hold each other responsible for being role models. It is a continuous aspirational stretch.

Chiudo con questo passaggio che sento molto vicino al mio pensiero:

There are companies where people ignore trash on the floor in the office, leaving it for someone else to pick it up, and there are companies where people in the office lean down to pick up the trash they see, as they would at home. We try hard to be the latter, a company where everyone feels a sense of responsibility to do the right thing to help the company at every juncture. Picking up the trash is the metaphor for taking care of problems, small and large, and never thinking “that’s not my job.” We don’t have rules about picking up the real or metaphoric trash. We try to create a sense of ownership so that this behavior comes naturally. Our goal is to inspire people more than manage them.

1,000 True Fans - Kevin Kelly

Kevin Kelly - conosciuto come KK - è uno scrittore molto famoso, co-fondatore di Wired, ma soprattutto profondo e lungimirante analista del mondo che ci circonda e dei suoi cambiamenti.

Questo pezzo, forse uno dei suoi più famosi in assoluto, è del 2008 e - come gli altri citati su questa pagina - continua a essere così rilevante che sono stati costruiti interi business sul concetto che esprime.

Che è molto semplice: per essere un creator di successo non servono milioni di fan, ne bastano 1000, ma convinti, veri. Con 1000 true fan potete "make a living out of it".

Un true fan è quello così innamorato del tuo modo di creare (che siano libri, fotografie, contenuti, app, aziende, canzoni, film) che comprerà sempre ogni cosa che produrrai.

A thousand customers is a whole lot more feasible to aim for than a million fans. Millions of paying fans is not a realistic goal to shoot for, especially when you are starting out. But a thousand fans is doable. You might even be able to remember a thousand names. If you added one new true fan per day, it’d only take a few years to gain a thousand.

Questo concetto, in particolare nella nostra epoca, diventa cruciale, non solo in quanto creator noi stessi, ma in quanto persone che non possono prescindere dalla conoscenza di queste dinamiche per rendere il proprio lavoro più efficiente ed efficace possibile.

Amazon's original 1997 letter to shareholders - Jeff Bezos

L'ultimo post che vi propongo è il primo che è stato scritto: è la lettera del 1997 scritta da Jeff Bezos agli shareholder di allora di Amazon.

Il contenuto non è particolarmente illuminante, ma per me è interessantissimo rivedere una realtà così rilevante come Amazon oggi, 25 anni fa, quando ancora l'ecommerce era una scommessa.

Sembra un po' assurdo letto ora, ma io lo trovo anche molto affascinante: è il potere dell'innovazione che cambia il mondo senza chiedere il permesso.

However, as we’ve long said, online bookselling, and online commerce in general, should prove to be a very large market, and it’s likely that a number of companies will see significant benefit. We feel good about what we’ve done, and even more excited about what we want to do.

[Bonus track] Life is short - Paul Graham

Metto questo come bonus track perché non contiene consigli su tecnologia, imprenditorialità o innovazione. Ma io lo trovo illuminante nella sua semplicità e nella linearità di pensiero - tipica di PG - con cui esprime questo concetto, banale ma fondamentale.

Life is short, as everyone knows. When I was a kid I used to wonder about this. Is life actually short, or are we really complaining about its finiteness? Would we be just as likely to feel life was short if we lived 10 times as long?

Then I had kids. That gave me a way to answer the question, and the answer is that life actually is short. You only get 52 weekends with your 2 year old. If Christmas-as-magic lasts from say ages 3 to 10, you only get to watch your child experience it 8 times. And while it's impossible to say what is a lot or a little of a continuous quantity like time, 8 is not a lot of something. If you had a handful of 8 peanuts, or a shelf of 8 books to choose from, the quantity would definitely seem limited, no matter what your lifespan was.

Ok, so life actually is short. Does it make any difference to know that? It has for me. It means arguments of the form "Life is too short for x" have great force.

When I ask myself what I've found life is too short for, the word that pops into my head is "bullshit."

If you ask yourself what you spend your time on that's bullshit, you probably already know the answer. Unnecessary meetings, pointless disputes, bureaucracy, posturing, dealing with other people's mistakes, traffic jams, addictive but unrewarding pastimes.

Leggetelo tutto perché merita, sapere di avere "solo" 8 Natali pieni di magia con i propri figli (per fare un esempio) mette tutto un po' più in prospettiva. Altro articolo bellissimo sempre sul tema è il famosissimo The Tail End.

Ma anche The days are long but the decades are short di Sam Altman.

Ok, ora ho proprio finito con la listona, spero che sia utile ai più curiosi di voi.

Per me sicuramente lo è perché ora posso mandare solo il link a questo articolo per suggerirli tutti in una volta sola 🤓

Ripeto l'appello iniziale: mi piacerebbe, se vi va, raccogliere anche i vostri spunti.

Quali sono gli articoli che secondo voi fanno parte della knowledge base fondamentale per un founder (o per chiunque si occupi di innovazione o investimenti)?

Infine: sharing is caring. Chi sono l'amico o la collega più curiosi che conoscete? Mandategli questo listone, così sapranno cosa fare sotto l'ombrellone o mentre sorseggiano una bella birra in un rifugio in montagna.

che super lavoro, utilissimo grazie!